Unlawful Detainer

Step by Step Detailed Explanation

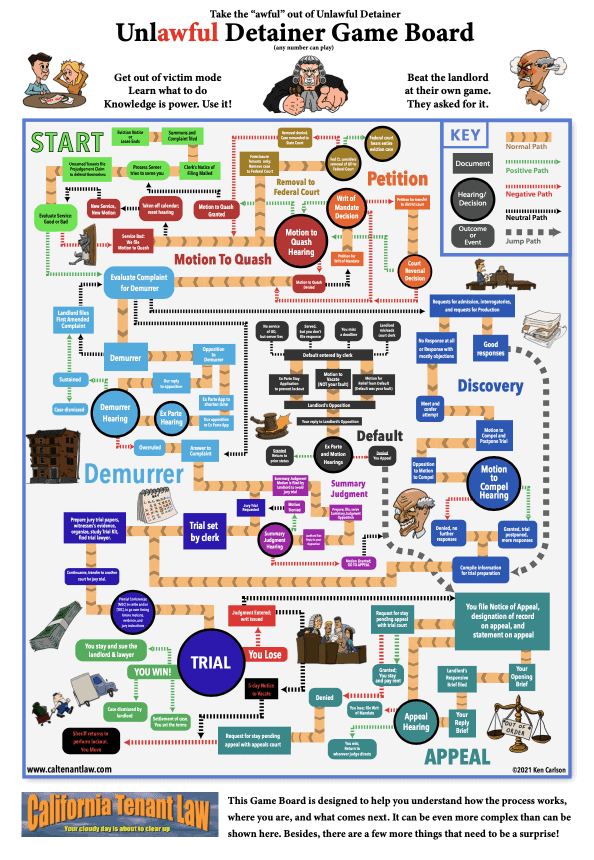

The Unlawful Detainer Game Board

This section is for those who love details and want to know as much as possible about how it works. Evictions are highly technical, as law goes. What seem like unimportant details can make all the difference, both in procedures and the substantive laws that affect your rights. Knowing how and when to apply the various strategies in your particular case is for the lawyer to decide. It’s far too much to explain on a website. Still, it benefits you to know the general lay of the land, so you know what is going on and what comes next.

Let the Games Begin

What the landlord is expecting is a short, simple process at nominal expense. His plan is for you to be out, maybe homeless, and blacklisted forever for having dared to defy him. Most tenants don’t stick up for themselves, or know what to do, or how to find effective legal help. Most tenants who have a valid case are still evicted, when they should not be. You are the exception.

When it comes to you, the landlord is not stepping on a cockroach; he is stepping on a landmine. The things you may have already done in reaction to the eviction notice are only the tip of the iceberg. Fighting the UD itself can prolong your occupancy for months or years, to where the landlord loses the property in foreclosure. All during the UD, you are paying no rent, the landlord has to cover the mortgage, taxes, etc., out of pocket and pay the lawyer to proceed. If the landlord is under siege from the governmental inspectors, bank, IRS, etc., the UD may lack the funding to proceed, and he has to dismiss it.

Here is the Unlawful Detainer Game Board, a flow chart to help you see what is going on and why this process takes so much time. You can download the PDF for free or buy a poster, which will be mailed to you. This section explains what you see on this Game Board. There are different phases of the UD in a typical case, which are depicted by the colors. The Key explains the shapes, like circles are court hearings.

START begins with the eviction notice, moving through the UD filing and attempted service of the summons and complaint on you. First, you want to avoid service of the eviction notice. If you don’t answer the door, they will probably just stick it on the door and walk away. Perfect! That’s their first mistake. The notice has an expiration date. If you do what the landlord demands by that date, the eviction stops, but you may have given up your rights.

If you don’t do what the notice demands, the landlord has to file the UD in court and then properly serve it on you. IMPORTANT: Once the notice expires, don’t answer the door. An unannounced visitor is probably the process server. The typically lazy process server just leaves the papers on the door or some other improper service. Another mistake. We want that improper service. An hour or so later, you can open the door, get the papers and then contact caltenantlaw.com for your next steps. The names of the papers are always given at the bottom, usually bold and all caps: Summons- Unlawful Detainer, Complaint-Unlawful Detainer, Prejudgment Claim of Right to Possession [PJCRP], and perhaps others.

If you live there but are not named as a Defendant, and you want to avoid being evicted, this is also the time for you to take action. The PJCRP is included in the papers to allow you to essentially “speak now or forever hold your peace.” These papers are supposed to be served on unnamed people by mail, posting a copy in a conspicuous place like the front door, and handing a copy to someone. That is rarely done, but the process server lies and says he did. You have 10 days from the service of those papers to file that PJCRP in court, which automatically adds you as a Defendant, and then you have to start filing your papers 5 days later. If you do not file the PJCRP in time, and the papers were served correctly according to the process server, you can lose that chance by “default” so if the Sheriff comes to evict the named defendants, you have to go, too. This is very important if the named Defendant does not live there or will not fight the case.

A Motion to Quash challenges that improper service. This is the time when you take over control of the UD case. Just filing it adds a minimum of 18 days to your time of possession, costs your landlord to oppose it, disappoints the landlord and his lawyer, and sets the stage for the next phases. Neither the landlord nor his lawyer were expecting it. You pulled the rug out from under them. Your landlord asks the lawyer how this could happen, and how much longer the eviction will take. The lawyer assures him that it will only be a little longer. That’s a lie. He knows.

Removal to Federal Court for qualifying cases interrupts that motion to quash just before the hearing. Your case can be “removed” to Federal District Court due to a “federal question” [e.g., CARES Act or PTFA, discussed later]. You literally “make a federal case out of it” when you file these papers. The removal happens just before the Motion to Quash hearing. It can add at least 45 days, and perhaps months, before it is sent back to State court for the Motion to Quash hearing.

Changing the Judge is next. UD judges are typically pro-landlord, if not completely corrupt. You want to have a fair hearing. In order to do that, we can exclude any Commissioner and one judge. We try to do this in the motion to quash, itself, but then the case may be transferred to yet another bad judge. Then the case has to be transferred to another judge willing to take the case. That change can take a few days, perhaps even longer.

The Motion to Quash Hearing itself is odd. You can’t file the motion unless you have the summons and complaint in hand, because you need to know the case number, party names, etc., to put on the motion you file. But the purpose of the motion is to say you didn’t receive it correctly as the law requires. The summons has to be either handed to you, or “substitute served” under strict rules. The only thing decided by the motion to quash is whether you were properly served with the summons and complaint. You don’t attend the motion to quash hearing; instead, you “submit on the papers.” If you attended, they would just serve you there and you would lose the benefit of challenging the bad service.

If the judge agrees with you, the landlord has to start over and re-serve the papers. If the judge disagrees with you, you still have about another 10 days to file your next response. We want the judge to illegally rule against you. It usually happens by the landlord’s lawyer’s prodding the judge to do so. You want to lose motion for an illegal reason, because then we have grounds to file a Petition for Writ of Mandate in the appellate court, and the UD is postponed even further. It is possible to have several successive motions to quash, in a loop, each time the landlord improperly tries to serve the UD papers.

The Petition for Writ of Mandate challenges the “mistakes” of the UD judge. There are a variety of errors commonly made, highly technical in nature, which backfire on the judge who was just trying to help the landlord evict you faster. The appellate court usually denies the Petition without saying why, but occasionally will agree with you and order the UD judge to change the quash ruling. The appellate court may even drag it out, themselves, setting a hearing to determine the issue, or order the UD judge to go through a special process that takes even longer. Just filing the Petition can add 15 days to 3 months to the UD process. If the appellate court agrees with you, you can then exclude the judge you appealed from participating any further in your case, and a search of yet another judge will be required.

It is possible to have more motions to quash after the Petition is resolved, and repeat that entire cycle, over and over, until the UD judge gets it right. All during that time, nothing further can happen in the UD, because the court does not have “jurisdiction” over you until that issue is resolved. Jurisdiction is the power of the court to make a ruling that affects you, all based in the US Constitution Due Process.

Discovery is the next in order. When it comes to trial, you don’t want to be surprised by the landlord making a claim that you could have shown to be a lie. To prevent that, you want to be prepared, and that is by using Discovery to find out before trial what the landlord claims. It is the most expensive part of the process, but well worth the money. You ask questions [“Interrogatories”], and request the landlord to admit things you think you can prove. You request the landlord to produce documents and other evidence that they have, which help you prove your case.

The landlord has to respond to your requests, but usually they make objections to avoid responding. Then, you have to file a motion to compel their answers after “meeting and conferring.” At the motion to compel, you are asking the judge to order the discovery to be produced, and award “sanctions” to make the landlord reimburse you for the expense of having to file the motion.

Armed with that Discovery information, you then know the landlord’s case, who the witnesses are, what evidence they have or don’t have, and especially how they responded to your claims. This also puts you in a stronger bargaining position for settlement. You want to get all this information even before you file your answer, and definitely before the “discovery cut-off” five days prior to trial. One of the ways you get that extra time to file the motion to compel is by filing a Demurrer instead of an Answer, as your next response to the Complaint.

The Demurrer is your first response to the Complaint, itself. The Complaint is an accusation. The demurrer attacks that accusation. It is not your side of the case, nor is it a trial. The Demurrer is only to determine whether the Complaint, as it is written, is technically OK, or if it needs corrections, like this:

- The complaint is not accusing you of doing anything wrong

- The complaint is not clear as to what you are accused of

- The complaint is not accusing you correctly

- The complaint is not filed by someone who has a right to file it

- The complaint is missing important parts of the accusation to be complete

- The complaint is filed against the wrong person

- The complaint is self-defeating by contradictory claims

- The complaint is filed while a prior claim for the same matter is still pending

- The complaint is not an eviction case, but something else

Just filing the demurrer, set for a hearing at least a month away, buys at least 5 more weeks, during which you can complete your Discovery. Normally, the judge “overrules” the demurrer [i.e., you lose the Demurrer], but occasionally the judge will “sustain” it [i.e., you win the Demurrer], and require the landlord to dismiss the case or correct the mistakes in the Complaint, if possible. The landlord’s lawyer may try to expedite the Demurrer hearing by an “ex parte application,” which you should oppose.

The Answer is finally your side of the case. In it, you deny all allegations in the Complaint, which then requires the landlord to prove each one. You also state “Affirmative Defenses,” which explain why you are right and the landlord is wrong. They can be the repeated points you raised in the Demurrer, as well as situations not mentioned in the Complaint.

In the first section of this article were some descriptions of the kinds of defenses you can raise to the various accusations. For example, to a 3-day notice to pay rent or quit, your defense might be that you legally spent the rent money fixing the property under Civil Code Section 1942. There are close to 100 different defenses to an eviction case, and you make the ones that apply your Affirmative Defenses.

If you have already filed an Answer in the case, you can file an Amended Answer, to correctly and more completely state your case. The sooner you do this, the better. What you filed as your initial Answer in a panic, or by the misdirection from the court clerk or a paralegal, does not seal your fate.

Requesting a Jury Trial is the most important part of your defense. It should be included in the Answer so that the court clerks don’t “lose” it. A jury trial is legally required in every eviction case, unless it is “waived” by failing to request it on time or pay the jury fees [or get a fee waiver for them]. Normally, tenants don’t request it, or the clerk falsely says that it can’t be done, it is just too expensive.

There are many good reasons for having a UD jury trial. Just requesting the jury trial gives you a tremendous tactical advantages:

- You can waive the jury on the day of trial and go with the assigned judge if you trust him/her.

- If you don’t request a jury up front, you can’t request one if you get stuck with a terrible judge.

- It will usually require an additional delay in the trial because another courtroom must be found.

- It usually delays trial because the lawyer must find 3-5 available days and reschedule other cases.

- It will usually require a different judge than the normal UD judge, a better chance at a fair trial.

- It can take the trial away from the pro-landlord judge, that the landlord was expecting.

- The jury is regular people who can sympathize with your situation, as well as apply the law.

- The landlord is already disappointed with his expensive lawyer being outwitted by his tenant.

- The landlord’s lawyer wants $10,000-$15,000 up front to do the jury trial, not wait for results.

- The landlord is reluctant to post such a large fee when his lawyer is such a disappointment.

- The landlord’s risk of losing by a jury, with all the evidence you have acquired, looks bleak.

- All the delays and expenses you have caused, have deflated your angry landlord’s ego.

- The landlord is fearful that you will have more tricks, that his lawyer was unprepared for

- You can bring in a lawyer on the day of trial, by surprise, which will really scare the landlord.

- You can do the jury trial yourself, with some coaching, and spare the expense of a lawyer.

- You walk in on the day of trial, confident, prepared, with all the papers, and the landlord caves.

If you have a fee waiver from the beginning, you file an Additional Fee Waiver request for the jury fee and the live court reporter fee. You have the right to a live court reporter, and not just the electronic recording that they want to foist on you. The clerk forgets to turn on the recorder, it doesn’t pick up what is being said, and it can’t be corrected to clarify what was not heard, unlike a live court reporter. Having the live court reporter also affects the availability and timing of the trial, causing further delays.

Summary Judgment is the landlord’s only hope against a jury trial. A Summary Judgment motion is greatly abused by landlord lawyers and the UD judges, so as to skip all the fair trial nonsense and get right to your demise. A summary judgment is designed only to eliminate cases with no possibility of winning. The landlord would have to show that they did everything right, and that none of your defenses have any chance at all. If there were 1,000 witnesses, photographs, and documents against you, and only your claims of what you know in opposition, you should win, because a jury would believe you and not them.

In deciding this motion, the judge is supposed to ignore everything the landlord claims and consider only what the tenant claims. The judge cannot “weigh” the evidence, or assess “credibility” of the tenant. When the judge rules on the summary judgment motion, he/she has to explain every disputed point and how the ruling was made. All doubts are required to be resolved in your favor, no matter how unlikely the judge may think they are. Unfortunately, the pro-landlord UD judges are more than happy to grant these motions, defy the law, and crush the tenants’ chances for a fair trial where they would have won. We are still working on that.

Trial

As complicated as it sounds, a jury trial is do-able by yourself with the right coaching and preparation. A non-jury trial is even simpler. Having done the discovery and knowing what the other side will say, you can quickly go over the points they admit, and expose the false claims they make with the evidence you have. You have seen jury trials on TV, and other than standing next to the witness for a two-shot, it is very much the same. You will have your exhibits in order, an outline of what you are going to present, and who is going to testify. Even cross-examination of the landlord is just picking out the facts and showing that there is more to the event than described, or the testimony is probably untrue.

Settlement

On the first day of trial, 90% of the cases we handle settle on terms favorable to the tenant. The landlord is disgusted with his lawyer and doesn’t want to pay for a jury trial. The landlord knows that if you win, he will be sued for trying to evict you and the enormity of the downside of this battle is stark. For all the arrogance and smugness in the beginning, and saber rattling in the middle, that disguise is worn through by the day of trial. It has been one disappointing and expensive experience after the next, for the landlord, and fear overcomes his aggressiveness. When you go to trial, have your settlement terms ready, and don’t be shy about demanding the moon. To the landlord, it is still the better choice.

Being Prepared

The landlord is expecting you to be terrified and unprepared. Instead, you walk in fully prepared, with all the paperwork ready to go, and confident if a bit nervous. We help you compile the witness and exhibit lists, the actual exhibits, jury instructions, a short introductory statement to the jury, and a proposed verdict form. We prepare all that for you. You can also have your opening and closing statements ready, an outline of your testimony to follow on the stand, and your cross-examination questions for the landlord ready. You know where you’re going to show him to be liar. It’s the landlord’s worst nightmare. You are prepared.

In contrast, 75% of the time the landlord’s lawyer has nothing ready, arrogantly thinking that you would be so afraid, that you would sign your life away in a settlement. The landlord’s lawyer nervously asks to see your papers, but you say you’ll exchange them only if he has his, and why doesn’t he? You make sure the landlord knows you are prepared, but the landlord’s expensive lawyer is not. You make sure the judge knows that, as well, and ask for a dismissal for lack of prosecution. It won’t be granted, but you made your point, and removed all remaining confidence from the landlord and his lawyer.

For those situations where the landlord’s lawyer does have their papers ready, you exchange the witness and exhibit lists, jury instructions, short statement to jury, and verdict form. Only if the judge orders it do you exchange actual exhibits. Occasionally, there will be “motions in limine,” which are intended to exclude some kinds of evidence. The landlord’s lawyer will typically have a settlement agreement to hand you, but you refused to sign it because it gives them everything and you nothing. You want trial.

Session with the Judge

For a jury trial, the initial session is just with the judge, to go over witnesses and exhibits, jury instructions, and when the trial will be heard. Sometimes the trial may only be afternoons for 5 days, not all in one session. The judge will order exchange of exhibits then, and identify how he wants the trial to proceed. The judge will consider the motions in limine and select the jury instructions. A prolandlord judge will disregard the tenant’s jury instructions, restrict the tenant’s evidence and otherwise try to sabotage the tenant’s case, so that the jury trial is converted to a kangaroo court. It happens.

At this time, the judge will also try to get the parties to settle, to save the court time. A pro-landlord judge will attempt to bully you into accepting the landlord’s terms, or tell you that you don’t have a chance to win. You thank the judge for his opinion, but continue to assert your right to a trial, unless you can make a counter-offer after consulting your lawyer and postpone the trial.

Jury Selection

After those preliminaries, the jury selection begins. Jurors enter the courtroom and sit in the audience where they hear the statement to the jury; some will be excused from participating. A random 14 people are selected, you are given a sheet with their names for you to make notes. Each side asks the jurors questions to identify any bias, experience, and understanding of cases like yours. The jurors may be conservative tenants, liberal landlords, or homeowners who have friends or family who have had landlord-tenant disputes. Each side will be able to “thank and excuse” a few jurors, who will then be replaced with others from the audience, whom you will question, and again select or reject. Once the jury is selected, the others in the audience go home, and the actual trial is usually set to begin the next day or after lunch.

The Trial, Itself

The Plaintiff gives his opening statement first, then it’s your turn. The opening statement is what you intend to prove. “The evidence will show that…” is the typical beginning of every sentence, as you tell the story about how it got to this. You can write this up and read it from the podium. With the opening statements, the jury then understands what this conflict is about, so they can appreciate the significance of the testimony and evidence about to be presented.

Following the opening statements, the testimony begins. Plaintiff goes first, presenting their entire case, and then “rests.” The Defendant goes next, challenging the Plaintiff’s case and presenting new facts, and rests when everything was said. The Plaintiff responds with a “Rebuttal” to challenge what the Defendant said, followed by a “Surrebuttal” by the Defendant, back and forth until everything is out.

After each witness testifies, the other side has the chance to “cross-examine” that witness by questions to expose inconsistencies, lies, contradictory evidence, and new facts within the “scope” of what that witness had said. You can tear the landlord apart on the stand with your cross-examination, leaving the judge and jury with a bad impression of the landlord. Be prepared to do just that.

After the testimony is completed, each side gives their closing statement. Defendant goes first, then Plaintiff. Right after that, the judge gives the jury instructions and the jury goes into the jury room to “deliberate” what they have heard and make their decision. When they come out, the verdict is announced and that is the end of the trial. There are technical things that can be done at that point, but they are rare.

Winning

If you win, you are not going to be evicted. The “rent” you would have paid if your landlord had not given the eviction notice, is not due, because there is no longer an agreement. You don’t pay the value of staying there as “damages” for unlawful detainer, either, because it has been determined that you were not unlawfully detaining. The losing landlord has to pay your attorney fees and costs, and you can then sue the landlord and his nasty lawyer for malicious prosecution for having tried to evict you. The landlord has to beg you to have a new rental agreement, or start all over to try to evict you some other way. It is a humiliating experience for the arrogant and belligerent landlord, which is something you can share with all the other tenants. Then, they will want to stand up against the landlord, too.

Losing

If you lose the case and do nothing further, the judgment leads to a writ of possession, which goes to the Sheriff. The Sheriff posts a 5-day Notice to Vacate on the door, and returns 6 days or more later to physically make you leave, posting a red notice that you can’t go back in. The Sheriff does not work on weekends or holidays. You have that 5 days to gather your things, put them in storage or move them somewhere, find a place, and move. If you have things that you were not able to remove before the lockout, the landlord has to protect them and give you the opportunity to come back and get them.

You can still appeal, win on appeal, and come back to trial before a different judge. You can also get a “stay of execution” [stopping the lockout] pending appeal, either from the trial court judge or the appeals court. That is granted on the condition that you pay the ongoing rental amount to the landlord pending appeal. If that stay is not granted, and you win on appeal, the landlord has to compensate you for all that you suffered pending appeal, before a dismissal can be entered. Otherwise, the case returns to trial after you win on appeal, you can counter-sue, and you can then win. It’s not over until it’s over.

Arrieta Claim

Even after a judgment, when the Sheriff is setting up the final lockout, you can stop it and even win the case in a second trial. You do it by filing a “Claim of Right to Possession” at the Sheriff’s office and within 2 days after that, in the court clerk’s office. Commonly called an “Arrieta claim,” it protects the rights of unnamed occupants [i.e. Does 1-10]. In simplest terms, it says, “Hey, what about me?” The Arrieta claim situation arises in 3 ways: (1) the PJCRP was never served, (2) a PJCRP was improperly served, or (3) it is a foreclosure eviction.

Like the PJCRP, discussed above, the Arrieta claim is intended to fulfill the Constitutional Due Process Right to Notice and an Opportunity to be Heard. You should not be evicted without having a chance to defend yourself. The PJCRP and Arrieta claims give you that chance, with the PJCRP before there is a judgment and the Arrieta claim afterwards.

How it Happens

In a normal case, the landlord doesn’t name everyone who lived there, just as with the PJCRP. It could be that the landlord sues only the tenant on the lease, but not her roommate, or even sues a tenant who is long gone, to really evict the ones remaining. Those who are not named in the lawsuit may not realize that they can fight the case, or that it is none of their business. They also may not have been served the PJCRP, or the PJCRP was not properly served. Despite what the tenants might have thought, if the PJCRP was not properly served, the judgment is only against the named Defendants, and the Sheriff has to serve the Arrieta claim with the Notice to Vacate. Realizing that this is their only chance to avoid being evicted, the unnamed tenants fill out and file the Arrieta claim.

In foreclosure evictions, usually only the foreclosed landlord is named as a defendant. These evictions are under a special set of laws. Accordingly, the Sheriff must include the Arrieta claim with the Notice to Vacate, in every case, even if the PJCRP was properly served and default of PJCRP claimants was entered. The tenants just do the filing and hearing as described above, and can then defend their case.

What it Does

- If the Arrieta claim is granted, that tenant is officially added as a Defendant, and can start the case from the beginning.

- From the time that the Arrieta claim is filed until after it is denied or the Arrieta claimant’s trial is held, everyone in the unit remains in possession.

- If there was no challenge to the judge or commissioner who handled the case so far, the Arrieta claimant can file a non-stipulation or peremptory challenge to get rid of that bad judge and get another who will be fair.

- If the Arrieta claimant then wins the case, the eviction is over and everyone stays.

- Where the named tenant was unfairly defaulted or lost by dirty tricks of the landlord or a judge’s ruling, having the Arrieta tenant being able to start fresh is, to use the theatrical term, Deus ex machina, for those whom it saves.

- It stops the lockout, at least temporarily, giving a defaulted tenant time to undo losing the case.

- At a minimum just from filing it, you gain a precious additional 2 weeks, giving everyone time to move out without being homeless.

How it Works

When the Sheriff serves the Notice to Vacate, and the Arrieta Claim is included with it, you can fill it out and file it in court. You make 3 copies of the Arrieta claim, and bring them to the Sheriff’s office that served the Notice to Vacate. The Sheriff needs to see some proof that you live there, like a driver’s license or utility bill. They keep a copy, and stamp your two. In the next two days, you then file the stamped Arrieta claim with the eviction court clerk, how keeps one and stamps the other and gives it back to you. Usually, the clerk will also assign a hearing date at that time. You must attend the hearing.

At the Arrieta hearing, the judge needs to be convinced that the person claiming to be a tenant really is. There is no specific set of evidence identified in the law. Some judges abuse their discretion to deny the Arrieta claim because the tenant did not provide “enough” evidence, without even saying what was missing. The judge is supposed to decide only on the evidence presented at the hearing, so if the tenant says he lives there and nobody denies that, the Arrieta claim should be granted. A driver’s license, bank statements, government papers, insurance, etc. showing the tenant’s address as the rental unit in question should be enough, without a rental agreement, because the agreement could be oral, or the tenant was never given a copy.

Default

Default is covered in the black section at the middle of the Game Board. Default is losing. You can lose in many ways, some are your fault, and some are not. Deadlines for eviction cases bring harsh results. If you are served with a notice or other legal papers and don’t respond in the correct way by the deadline, you can lose the case by “default.” If you were late for the court trial because you were looking for a parking space or were stuck in traffic, default results. Default can also occur if the court clerk prematurely enters your default in the court system because the landlord asked her to do it. It can occur because the judge who wants to help the landlord illegally declares your default.

Default is not the end of the world, nor of the case. It can be undone. You can un-lose. You just need to take action quickly. There are two ways to undo a default: if it was your mistake, you file a Motion for Relief from Default. If it was the court’s mistake, you file a Motion to Vacate.

Motion for Relief from Default

The motion for relief essentially says “I goofed up, but for a valid reason,” and is accompanied by any papers that you missed filing. It is supposed to be granted if the default was by “surprise, inadvertence, or excusable neglect.” Missing the bus, mis-calendaring the event, not finding the papers, not understanding what was to be done, being misdirected by a court clerk or quack paralegal, filing the wrong papers or in the wrong place, are all examples of reasons for which the motion should be granted, restoring you to where you should have been.

Motion to Vacate Default

In contrast, the motion to vacate is to undo the default that is not your fault. It is usually the result of the sneaky landlord’s lawyer intentionally requesting a premature default. Most common is where you filed a motion to quash or petition for writ of mandate, but the clerk entered your default because the landlord requested it. Since “entry” of default is done by the court clerk, the error is usually found there. The incompetence of the court clerks is notorious. The landlord exploits that. Sometimes, it is the judge who erroneously orders a default, because of ignorance or corruption or both. The motion to vacate has to show that you did things correctly, the mistake by the clerk or judge, and the incorrect default that resulted. Unlike the motion for relief, the motion to vacate does not need to be accompanied by any other papers than the exhibits to it showing the mistakes.

Ex Parte Stay – Stopping the Lockout

Despite all the other short times for UD hearings, these two motions are still set out at least 4 weeks ahead. By that time, the judgment will be entered on your default and you will be evicted. In order to prevent that from happening, you need to file an Ex Parte Application for Stay and Shortening Time with your motion for relief or motion to vacate. If granted, the judge stops the lockout and sets a short time for your hearing, so that you won’t be locked out before the motion is heard.

You give telephonic notice to the landlord’s lawyer on the day before you intend to talk to the judge about the Ex Parte. [“Ex Parte Notice”] You then file the papers with the courthouse by their rules, either the day before or some time shortly before the hearing. Then you attend the hearing to talk to the judge. If granted, notice needs to be given to the Sheriff to stop the lockout, and your motion hearing is set some time sooner than you were required to set it.

Where you have a valid basis for your motion, the judge can save time and grant your ex parte and motion, and put things back on track. That is usually what happens. The law requires cases to be heard on the merits and to overlook technicalities such as defaults, wherever it is fair. In a motion for relief, it can include as a condition that the tenant pay some money for the delay or the lawyer’s costs, but that is better than losing your chance at trial and being evicted.